“SIKKIM FOR SIKKIMESE”

NO SEAT, NO VOTE

‘Merger’ was conditional

“It is not

right and proper to marginalize the original inhabitants of Sikkim or the three

ethnic communities politically and economically through inclusion of other

groups within the definition of ‘Sikkimese’….

While others

fought the elections we fought for our people. We were not concerned with who

wins or loses in the polls; our main concern was that if the Assembly seats

were not restored to us in the near future we would be the ultimate losers and

the electoral process would then become a meaningless ritual as the Sikkimese

people would have no future to look forward to.”

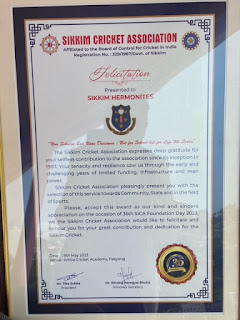

The 12-hour hunger strike by

Sikkimese representatives at the ‘BL House’, Gangtok, on October 2, 1999. (Left to Right) Tenzing

Namgyal, Jigme N Kazi, Nima Lepcha, Pintso Bhutia, KC Pradhan and Gyamsay Bhutia.

“Despite

trying circumstances in the last years of the Namgyal Dynasty, Chogyal Palden

Thondup Namgyal never gave up. He never surrendered. Why should we despair and

yield ourselves to forces that wish to erase us from the face of the earth? The

Chogyal lost everything – his kingdom, his power, his flag and finally his own

family. And in the last days of his life he was betrayed by his friends,

supporters and those whom he trusted and

confided in. And yet he struggled on and never gave up for he believed in a

cause worth fighting and dying for – a cause much greater than life itself.

History is not always written by the conquerors but sometimes by its victims

and followers of those whose lives are a testimony of courage, honour, patience

and sacrifice.

For the true Sikkimese, May 16, 1975

heralded the end of an era and perhaps the beginning of a new struggle to

preserve ‘Sikkim for Sikkimese’; but, this time, within the bounds of India, a

great nation ruled by petty politicians and corrupt bureaucrats. This was an

ideal that inspired me and shaped the course of my life ever since I returned

to my native land at the end of 1982 after nearly twenty years.

To aim high, think big and struggle for a

worthy cause – for unity, identity and a common destiny for all people in

Sikkim – was the agenda that I had set for myself both in my profession and later

on in politics. Anything less than that was totally unacceptable to me and not

worth the risk, toil and the endless struggle that lasted for more than two

decades.

By the end of 1999 – the last year of the

20th century – I felt a certain sense of restlessness and impatience that I

hadn’t experienced before. I needed and wanted to step out of the narrow

confines of my profession and free myself to openly and directly place my views

to the outside world on certain issues of public interest which were close to

my heart and which guided my professional and political outlook for a long,

long time.

Journalism does not allow you to mingle

personal feelings and political inclinations with professional duties. The

respect that I had for my profession had one disadvantage – it became a wall

between me and my people. While freeing me in some ways it also enslaved me. I

could not remain in the cage any longer – I needed and wanted to come out and

set myself free. I could not and would not allow my precious dream to die in

the hands of petty politicians without getting personally and politically

involved in the struggle towards achieving my goals.

Even if

I face defeat my effort and struggle to pursue my dream would be worthwhile. I

will not feel guilty of playing it safe and shying away in my neat little

corner when the ideal thing to do was to come out in the open and take your

stand - come what may! Those who knew me

well, respected me, and had great faith and trust in my capacity and commitment

had no doubt about the honesty of my heart and the righteousness of my cause

that drove me to place my case to the outside world.

It was US President Theodore Roosevelt who

once said: “The credit belongs to the man who is actually in the arena - whose

face is marred by dust and sweat and blood...who knows the great enthusiams,

the great devotions - and spends himself in a worthy cause - who at best if he

wins knows the thrill of high achievement - and if he fails at least fails

while daring greatly - so that his place shall never be with those cold and timid

souls who know neither victory or defeat.”

In the autumn of 1999 I found myself in direct

confrontation with the political establishment on issues that were close to my

heart for a long time. You either take a stand and live out your dream or just

talk about it, write about it but actually do nothing about it and spend the

rest of your days regretting for not having spoken up and making your stand

clear to the whole wide world. The fact is you are what you do and not what you

want to do. The road to hell is certainly paved with good intentions. Our

leaders who preach and do not practise should know where we are heading.

In mid-September 1999, I, as the Chairman of

the Organisation of Sikkimese Unity (OSU), supported a call for boycotting the

ensuing Assembly elections in the State, scheduled for October 3, 1999. Though

I had written about it earlier we actually did not make any plan to take such a

radical step on the Assembly seat reservation issue. It just happened – quite

spontaneously and to my great delight! The boycott call given by the Sikkim

Bhutia-Lepcha Apex Committee (SIBLAC) – the apex body of the indigenous Bhutia-Lepchas

in the State – was in reaction to the betrayal of people’s trust by the combined

political leadership of the State and the Centre on the Assembly seat issue.

The 1999 Assembly polls was the fifth

Assembly elections in Sikkim since the arbitrary, undemocratic, unjust and

abrupt abolition of Assembly seats reserved for the three ethnic communities in

1979. Not only were the political parties in the State fooling the people on

the seat issue the Centre also refused to respond favourably and timely on the

demand for restoration of the political rights of the Sikkimese people as per assurances

given to them during the merger, which are reflected in the historic Tripartite

Agreement of May 8, 1973 and Article 371F of the Constitution.

The boycott call on the Assembly and Lok

Sabha polls was given on September 12, 1999 when the SIBLAC held an impressive

rally in the State capital. Former General Secretary of Denzong Yargay Chogpa,

Tashi Fonpo – a Bhutia – and former President of NEBULA (an organization for

Nepali, Bhutia and Lepcha unity) – Nima Lepcha – were elected ad-hoc convenors

of the SIBLAC before the rally.

The SIBLAC also called for a one-day token

hunger strike on October 2, a day before the polling date which was also a

public holiday in India to celebrate the birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi,

widely revered as the ‘Father of the Nation.’ The decision to hold the rally,

boycott the polls and stage a one-day hunger strike was decided by both the SIBLAC

and OSU although the apex committee of the Bhutia-Lepchas, by virtue of its

influence and popularity among the minority community, played a leading role in

the given situation.

While demanding restoration of their

political rights as per the historic May 8, 1973 Tripartite Agreement and

Article 371F of the Constitution, the newly-formed body also expressed its

resentment against political parties such as the ruling SDF and opposition

Sikkim Sangram Parishad (SSP) for fielding non-Sikkimese Bhutia-Lepchas (BLs)

from the 12 reserved seats meant for ‘Sikkimese’ BLs. The SIBLAC appealed to

all BL candidates – intending to contest the ensuing polls – to boycott the

polls to register their protest. It also appealed to the Sikkimese Nepalese to

support its demand on restoration of their political rights.

Apart from the OSU, prominent among the BL

and tribal organizations, which participated in the rally calling for poll

boycott, were Lho-Mon Chodrul, Sikkimese Unity Joint Action Committee, Sikkim

Tribal Women Welfare Association, Sikkim Lepcha Association and Denzong Gyalrab

Sungkyab Tsodyo.

The ‘Newar Guthi’, the premier social

organization of the Newar community in the State, was the first Nepali

organization to support the SIBLAC’s demand on seat reservation in the

Assembly. The Newar Guthi President and former chief secretary of Sikkim,

Keshab Chandra Pradhan, while expressing his appreciation and support for the

stand taken by the SIBLAC, urged the minority community to demand inclusion of

Sikkimese Nepalese in the list of Scheduled Tribes in the State. In a letter

dated September 16, 1999 to the SIBLAC, Pradhan said if this demand was met it

would not only lead to declaration of Sikkim as a ‘Tribal State’ but seats in

the Assembly would also be restored to the Sikkimese Nepalese. The former chief

secretary said the Newar Guthi “is consistent of the view that the provision of

Article 371F, which imparts distinct identity to three ethnic communities in

the State, is being gradually diluted during the last twenty years.”

The Newar Guthi President emphasized the

need “to reweave the fine Sikkimese fabric and bring about a trust, amity and

goodwill among sections of the community so vital in this sensitive border

State. This was in fact the basic spirit and objective behind the Article 371F

when it was initially framed.”

Supporting the SIBLAC’s call for poll

boycott, the OSU on September 15, 1999, made a public appeal demanding

“withdrawal of nomination papers filed by bonafide Sikkimese and other

candidates who are contesting the coming elections on October 3.” The OSU’s Press

statement further added: “Politicians and political parties have been given 20 years

to restore the political rights of the Sikkimese people. They have failed miserably. They should now

not be given another chance to fool the people. They should take a break and

leave it to the people to decide their future course of action on the seat

issue.”

The sudden revolt amongst the minority BLs

and their decision to boycott the polls was prompted by the SSP and SDF’s

decision to field Sherpa candidates from Rakdong-Tintek constituency in East

Sikkim, which is one of the 12 Assembly constituencies reserved for ‘Sikkimese

Bhutia-Lepchas’. The Constitution (Sikkim) Scheduled Tribes Order of 1978

includes Sherpas, traditionally regarded as belonging to the Nepali community, within

the definition of ‘Bhutia’ in Sikkim. The Representation of People Act 1980,

while referring to the 1978 Scheduled Tribes Order, permits Sherpas and other

scheduled tribes in Sikkim, listed in the ’78 Order, to contest from the 12

reserved seats meant for ‘Sikkimese Bhutia-Lepchas.’ This is because the new

entrants to the ST list in the State fall within the definition of ‘Bhutia’ in

the 1978 Order.

The clubbing of 8 communities such as

Chumbipa, Dopthapa, Dukpa, Kagaty, Sherpa, Tibetan, Tromopa and Yolmo within the

definition of ‘Sikkimese Bhutia’ has been opposed by the indigenous Bhutia-Lepchas,

who are against further dilution of their original identity and erosion of

their political rights. It may be pointed out that the BLs are not against the

eight communities being referred to as ‘Bhutia’ as elsewhere in the Himalayan

region some of these communities are clubbed - and rightly so - under the

broader category of ‘Bhutia’.

The objection raised by Sikkimese

Bhutia-Lepchas is that these communities cannot fall under the traditional

definition of ‘Sikkimese Bhutia’ – the emphasis is on the word ‘Sikkimese’ and

not ‘Bhutia.’ For instance, many people in the region, particularly the

Nepalese, refer to Tibetans and Sikkimese Bhutias as ‘Bho-te’. Sometimes the

Tibetans from Tibet are referred to as ‘Chin-Bhote’ and Bhutias from Sikkim as

‘Sikkimey Bhote’, meaning Bhutias from China (Tibet) and Bhutias from Sikkim

respectively. Hence, the emphasis on the above context is on one’s nationality,

territory and origin and not religion, language or community.

The same argument may be brought forward

while defending the unique and distinct identity of the ‘Sikkimese Nepalese.’

Sometimes the expression ‘Nepali of Sikkimese origin’ is used to distinguish

between ‘Indian Nepalese’, ‘Sikkimese Nepalese’ and Nepalese from Nepal. It

must be borne in mind that one of the basic criteria for grant of citizenship

is one’s origin. Therefore, in both cases it is not right and proper to

marginalize the original inhabitants of Sikkim or the three ethnic communities

politically and economically through inclusion of other groups within the

definition of ‘Sikkimese’.

The

Sikkimese people have been very generous, open and broadminded in dealing with

non-Sikkimese residing in the State. What they expect in return is to view the

present situation in a more positive way and display some amount of care and

concern towards the growing feeling of insecurity and apprehension amongst bonafide

Sikkimese for their very survival in the land of their origin. The Sikkimese

people do not want to become refugees in their own homeland. In every country or continent governments

enact laws and frame rules to protect their own citizens. Why should the Sikkimese

people be expected to always accommodate each and every individual who come to

Sikkim and in the process risk losing their own rights, interests and identity.

Open revolt broke out within the SSP when

the Bhutia-Lepcha leadership in the party challenged Bhandari on the choice of

BL candidates for the October Assembly elections. Bhandari’s decision to give

party ticket to former Health Minister O.T. Bhutia from the Rumtek constitutency

(reserved for BLs) in East Sikkim led to the resignation of three prominent BL

leaders – Nima Lepcha, R.W. Tenzing and Sonam Lachungpa – from the SSP. What

made matters worse was Bhandari’s renomination of the sitting SSP MLA, Mingma

Sherpa, from Rakdong-Tintek constituency in East Sikkim, which was reserved for

the indigenous Bhutia-Lepchas.

Former minister and BL heavyweight Sonam

Tshering, who was expecting the SSP ticket from his home constituency of

Rakdong-Tintek, was ditched at the last moment and this deeply hurt BL

sentiments. The BLs expected Bhandari to seize the opportunity and honour his commitment

on the Assembly seat issue but they felt let down again. Till the nomination of

party candidates the SSP was doing extremely well in its poll campaign.

Bhandari himself was pretty certain that he would make a comeback.

The fact that the SSP chose only two Lepcha

candidates from the 12 reserved seats of the BLs made matters worse. The Bhutias,

too, felt let down as Bhandari selected only lightweights who were loyal to

him. Gradually, a similar pattern also began to emerge in the choice of BL candidates

in the ruling party. There, too, BL stalwarts were ignored or eliminated from

contesting the polls through devious means.

My editorial in the Observer (Sept 25-29, 1999) reflected the mood within the minority

community: “Not only were the Lepchas thoroughly disgusted with the

discriminatory way in which the SSP leadership distributed party tickets, even

the Bhutias, who had a major share, were disillusioned. The SDF was expected to

capitalize on Bhandari’s failure but when it, too, fielded a Sherpa candidate

from Rakdong-Tintek, doubts and apprehension among the BLs surfaced.

Furthermore, fielding of 4 Sherpa candidates from Ralong, where SDF stalwart,

D.D. Bhutia, is contesting also sent conflicting signals to the people.”

I reiterated the importance of the political

leadership in the State to allot party tickets to bonafide Sikkimese from the

three ethnic communities to contest from the 32 seats in the Assembly. If we

genuinely and sincerely believe in our declared policy on the Assembly seat

issue then it should be reflected in the choice of our candidates. Until the

Assembly seat issue is resolved to our satisfaction major political parties,

which demand restoration of the political rights of the Sikkimese people as per

Article 371F of the Constitution, must field bonafide Sikkimese BLs from the 13

seats, including the lone reserved seat of the Sangha, and bonafide Sikkimese

Nepalese from the 17 general seats and the 2 seats reserved for the Scheduled

Castes in the State.

Any deviation from this stand in the name of

political expediency would be harmful for preservation of Sikkimese unity,

identity and communal harmony. The need to view the October 1999 Assembly polls

from this perspective was emphasized in the OSU’s appeal on August 26, 1999,

when the entire State observed the annual Pang Lhabsol festival, worship of

Khangchendzonga, the Guardian Deity of Sikkim:

“Two decades and six years back the

Sikkimese people signed a historic pact on May 8, 1973. Leaders of three major

political parties, representing the three ethnic communities of Sikkim –

Lepchas, Bhutias and Nepalese – signed the Tripartite Agreement on May 8, 1973.

The signing of this historic Agreement, which reflected the will of the Sikkimese

people, was witnessed by the Chogyal of Sikkim and representatives of the

Government of India, who were also signatories to this accord. The 1973

Agreement fully protected the political rights of the bonafide Sikkimese

people. The Government of Sikkim Act 1974 and Article 371F of the Constitution,

which provide special status to Sikkim, reflect the spirit of the May 8

Agreement and the Kabi-Longtsok pact.

On this historic day of Pang Lhabsol (August

26, 1999), being observed as Sikkimese Unity Day, let us renew our pledge to

foster peace, unity and harmony. Seven centuries back in the latter half of the

13th century our ancestors swore eternal blood-brotherhood pact on this day. The

Guardian Deities of Sikkim and the Sikkimese people, who belong to the three

ethnic communities, were witnesses to this historic oath-taking ceremony”.

The appeal added: “This treaty of peace, unity

and harmony among the Sikkimese people remained intact over the centuries till

two and half decades back when the Kingdom of Sikkim became a part of the Indian

Union in 1975. As we enter the next millennium let us not only look back to

where we have come from but let us look forward and renew our pledge for a

common destiny.

There can be no better way to preserve our unity

and identity without the fulfillment of our demand for restoration of our

political rights which were taken away prior to the first elections after the

merger. The Sikkimese people have the right to preserve their distinct identity

within the framework of the Constitution as enshrined in Article 371F.”

I placed on record that since the Assembly

seat issue had the support of the people it cannot be ignored so easily:

“Restoration of the Assembly seat reservation of the three ethnic communities

in the State have been raised by the combined political leadership in the State

in the past two decades. In the four consecutive Assembly elections the

Assembly seat issue has been a major political issue of all major political

parties in Sikkim. In this election, too, the seat reservation issue continues

to be a major political issue. But despite having given top priority on the

issue by successive state governments the Centre has failed to concede to this

long-pending demand of the Sikkimese people. Inspite of the Centre’s delay in meeting

the just demand of the people there is the need for us to work unitedly to

achieve our common objective for restoration of our political rights.”

The need for the political leadership in the

State to genuinely and sincerely respect the sentiments of the people and

implement its policies on the seat issue, pending the final resolution of the

demand, was also stressed: “Pending the disposal of the seat reservation demand

it is the political leadership in Sikkim which must respect the sentiments of the

people on the issue. Those who genuinely believe in the fight for restoration

of the political rights of the Sikkimese people ought to field bonafide

Sikkimese candidates in the 32 Assembly constituencies and the lone Lok Sabha

seat.”

I

reiterated: “It is not too late to take a principled stand on the basic

political rights of the people. Let us not trample upon the sacred rights of

the people in our blind pursuit for power. There is no better way to convince

the Centre and the people of Sikkim of our genuineness on the seat issue than

rigidly implementing what we have in mind on this vital issue in the coming

elections. The time has come for each one us to make our stand loud and clear

on the issue. The allotment of seats to various candidates by the political

leadership in the State will be taken as an outward indication of our inner

conviction. In the process each individual politician and their parties stand

to gain or lose from the stand they have taken.”

Was it only me who was taking the seat issue

so seriously? I begin to think over this and wondered without pausing for an

answer. In June 1999, four months before the Assembly polls, I highlighted the

need to take radical steps on the seat issue if it still remained unresolved.

Captioned ‘No Seat, No Vote’, the Observer’s

editorial, dated June 5-11, 1999, stated:

“Mere reiteration of the seat issue demand

on special occasions becomes only a symbolic ritual which our politicians are

good at. Lack of concrete strategy to meet the demand reflects the political will

of the political establishment…That the abolition of the basic political rights

of the Sikkimese took place four years after the controversial ‘merger’

suggests that New Delhi blatantly violated the terms of Sikkim’s integration

with India…If perceived closely none of the 32 seats in the House and the two

seats in the Parliament are reserved exclusively for Sikkimese. This indeed is

a blatant act of betrayal. Because of this non-Sikkimese have found a place in

the House much to the detriment of bonafide Sikkimese who are largely Sikkimese

Nepalese.”

I even hinted on the need to boycott the

polls if New Delhi remained adamant on preserving status quo on the seat issue:

“The political leadership in the State needs to take the seat reservation issue

more seriously. Mere adoption of this basic demand in their party resolution

and manifesto will not do. This demand has been raised at appropriate fora for

nearly 25 years now. If the Centre fails to act positively on this vital demand

then the Sikkimese people need to do some rethinking.”

I added: “Erosion of Sikkim’s distinct identity

within the Union through violation of ‘merger terms’ cannot and should not be

tolerated any longer. If political parties fail to get this demand met then the

Sikkimese people may resort to the last option of boycotting Assembly and Lok

Sabha polls in the State. Democracy provides an opportunity to the people to

exercise or not to exercise their franchise. If the need arises the Sikkimese

people can send empty ballot boxes to New Delhi during the elections. By doing

this they will not only be merely implementing the oft-repeated slogan – ‘No

Seat, No Vote’ – but would have also sent the ultimate message to the

Government of India.”

The

OSU leader and former minister of the L.D. Kazi Government (1974-1979), K.C.

Pradhan, submitted a ‘7-Point Charter of Demand’ to the President of India in

July 1999, demanding formation of a high-level committee to look into “the seat

reservation issue before the situation gets out of hand.” Pradhan - perhaps the

key figure and the main leader of the Nepalese during the merger era - who was

also one of the main signatories to the historic May 8, 1973 Tripartite

Agreement, warned: “Continued violation of the terms of merger and deprivation

of the political rights of the Sikkimese people cannot be tolerated any

longer.” He sent an ultimatum on the seat issue: “The basic political rights of

the Sikkimese people must be restored before April 2000 when Sikkim completes

25 years as an Indian State.”

Pradhan

added: “I have from time to time made several representations to the concerned

authorities in Delhi and Gangtok about the deteriorating political situation in

the State but so far the plight and problems of the Sikkimese people have been

ignored. Unfortunately, Delhi continues to ignore my warnings. If the situation

is not handled carefully and timely Sikkim will head towards political

uncertainty at the dawn of the next millennium. This is neither in the interest

of the Sikkimese people nor the nation’s security interests in the region.”

Pradhan’s stand on the seat issue is

consistent with the OSU’s views on the said issue. As early as January 1998, I

– as OSU Chairman – made a Press statement urging the Centre to restore the seats

by April 2000, when Sikkim completes 25 years as a State of India: “Merger with

the world’s largest democracy twenty-three years ago would be meaningless if

the Sikkimese people are deprived of their fundamental and constitutional

rights.”

I pointed out: “Ever since the merger in

1975 political leadership in the State has been constantly harping on the need

for the Centre to respect and honour the ‘terms of the merger’ but the

authorities in Delhi are yet to respond positively and decisively on major

issues that concern the Sikkimese people…We have waited for more than two

decades for restoration of our political rights and this cannot go on forever.

By the turn of the century Sikkim will complete 25 years as part of the Indian

Union. The Centre must immediately initiate moves to restore Assembly seats for

the Sikkimese and the legal and constitutional process on this issue should be

completed by the end of 1999.”

Pradhan’s 7-Point demand included revision

of voters list on the basis of 1974 electoral rolls – which had names of only

‘Sikkim Subjects’, delimitation of Assembly constituencies, and safeguards for

‘other Sikkimese’, meaning those other than ‘original Sikkimese’ residing in

the State such as members of the old business community and others.

My last call before the October 1999

Assembly polls on the seat issue featured in the editorial of the Observer, dated September 18-21, 1999,

and captioned “Total Revolution” – ‘No Reservation, No Election’: “It is

significant to note that the BL Apex body has now urged the larger Sikkimese

Nepalese community to back their demand and give them the much-needed support.

Wounded by the failure of the political leadership among the Nepalese community

to respect their political rights, pending the finalization of the Assembly

seat issue, the BLs have now turned towards the Sikkimese Nepalese people

themselves and others to come to their aid. In a democracy, it is the majority

community which must rule but protections and safeguards must be provided to

the minority community. In their lust for power the political leadership in

Sikkim are (is) forgetting and ignoring the just demands of the people and are

(is) deliberately trampling over their political rights and thereby hurting the

sentiments of the people. No political party in the State has the mandate to

further divide the people, dilute their political rights and cause social

disharmony and political instability in this strategic border State.”

The editorial added: “It is now up to the

Sikkimese people to come forward and respect the sentiments of their brothers

and sisters in distress. The BLs are confident that their hope placed on the

larger community will get the right response. But while the BLs desire and

expect support from the Sikkimese Nepalese they must also realize that the

majority community, too, are in a fix and are demanding restoration of their

reserved seats in the Assembly and should be prepared to fight unitedly for

restoration of the political rights of all Sikkimese.

Time is running out and the Sikkimese Nepalese

cannot now afford to pin their hopes on the politicians for their long-term

interest. There are no easy answers to the political uncertainty faced by the

Sikkimese masses. By calling for boycott the BLs have shown that elections are

no solutions to the political crisis faced by the Sikkimese people. Making

representations to the concerned authorities, be it in Gangtok or New Delhi, is

not enough. For the past 20 years various social and political organizations

have rightly demanded restoration of the Assembly seats for the Sikkimese

people.”

The editorial concluded: “Memoranda after

memoranda have been submitted on the issue but what has been the net result of

all these endeavours? While political rhetoric on the issue continues the seat

issue is yet to be resolved. Any further violations of the terms of the merger

cannot and must not be tolerated any longer. By keeping the issue perpetually

pending the political leadership, in collaboration with New Delhi, are

gradually leading the Sikkimese people to political suicide…There cannot be

more articulate and eloquent way of expressing the total sense of frustration

and resentment over the continued violation of the merger accord and abuse of

the people’s mandate than to take a firm step on the issue and boycott the

coming elections in the State.”

Though our appeal for total boycott of the

polls was serious and genuine we were aware of the fact that the appeal – made

at the last moment – would not be well received by political parties which were

totally engrossed in the poll process. This was quite understandable although

they should realize by now the importance of adopting a strong stand on the

seat issue if they are at all serious about the future of Sikkim and the

Sikkimese people.

Our stand at that stage was symbolic but the

message and the spirit in which we chose to adopt this stand would be welcomed

by the people. And yet we were delighted when the Congress (I) candidate,

Tseten Lepcha, from my own home constituency of Lachen-Mangshilla, North

Sikkim, withdrew his nomination papers in response to our appeal. Lepcha may

have played his cards well during the polls and killed many birds with one

stone but his gesture was significant and appreciated by the people.

He told reporters that in view of the

pre-poll developments on the seat issue he felt it was his bounden duty not to

take part in the polls in order “to protest, to express our deep anguish and to

prove that if the need arises, the Lepchas are prepared to make the supreme

sacrifice to fight for our cause.” It is also significant that these words come

from the son of a former MLA from the tribal-dominated north district, Tasa

Tingay Lepcha, who earlier contested and won from the Lachen-Mangshilla

constituency. Majority of voters in this constituency, which had a sizable

number of Limbus, were BLs.

Just days before the scheduled date of the

proposed hunger strike on October 2, 1999, the OSU and SIBLAC formed the

Sikkimese Nepalese Apex Committee (SNAC) in Geyzing, West Sikkim. The new body

was formed at a joint meeting of the OSU and SIBLAC and was chaired by K.C.

Pradhan. Buddhilal Khamdak, a young and educated Nepali from the Limbu community

in West Sikkim, was made the SNAC’s Convenor. The newly-formed body supported the

seat issue demand raised by the SIBLAC and OSU and urged the two organisations

to support the demand on restoration of Assembly seats of the Sikkimese

Nepalese.

On October 2, while the rest of the nation

celebrated the 130th birth anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi (Gandhi Jayanti), the

Sikkimese people – represented by SIBLAC, OSU and SNAC – sought the blessing of

the ‘Father of the Nation’ and the Guardian Deities of Sikkim in their struggle

on restoration of their political rights. The 12-hour hunger strike by six representatives

of the three ethnic communities at the ‘BL House’ in Gangtok on October 2

symbolically ushered in a new phase in the fight for restoration of the

political rights of bonafide Sikkimese belonging to the three ethnic

communities.

Four members of

the SIBLAC – two convenors (Nima Lepcha and Pintso Bhutia), Vice-Convenor

Tenzing Namgyal, and a woman representative (Gyamsay Bhutia), the SNAC Advisor

K.C. Pradhan and myself as OSU Chairman took part in the historic one-day

hunger strike on October 2, 1999.

We had actually chosen the premises where

the ‘Statues of Unity’ are installed for the venue of the one-day hunger

strike. Located in the heart of the capital at the northern end of the Mahatma

Gandhi Marg – the main market area in the capital – this venue would have been

the ideal place to begin a prolonged and intensive campaign on the seat issue.

However, the State Government refused to allow us to use this place. In fact,

it asked us to call off the hunger strike and the boycott call.

In a

letter to the SIBLAC, dated September 17, 1999, Chief Secretary Sonam Wangdi

said redressal of grievances should be done through participation in the

electoral process and pointed out that boycott of elections “is the last action

to be taken as the final resort when all other means have failed.” The Chief

Secretary simply could not see that we had resorted to this method as “all

other means”, including the electoral process, in the past two decades failed

to achieve the desired result. We ignored the government’s plea and went ahead

with the hunger strike.

However, it must be placed on record that if

it hadn’t been for the OSU the hunger strike and boycott call may have been put

off. Pradhan and I tactfully and very firmly exerted enough pressure on the

SIBLAC leadership, which was dithering on the issue at the last moment when

they were under extreme pressure. Even if the SIBLAC had backed off at the last

moment the OSU and SNAC would have certainly continued with the mission. No

amount of tactics and pressure would work on Pradhan and me and on this we were

very confident.

As planned, we held the hunger strike on

October 2 to remind the world that we were determined to struggle on till our

demand on restoration of our political rights were met. While

others fought the elections we fought for our people. We were not concerned with

who wins or loses in the polls; our main concern was that if the Assembly seats

were not restored to us in the near future we would be the ultimate losers and

the electoral process would then become a meaningless ritual as the Sikkimese

people would have no future to look forward to.

(Ref: The

Lone Warrior: Exiled In My Homeland, Jigme N. Kazi, Hill Media

Publications, 2014, Sikkim Observer and Blog: jigmenkazisikkim.blospot.com.)